Dinner and Discussion, July 2025

One of our favorite events to host is Dinner and Discussion: an evening where Stan cooks something delicious, we invite smart people over, and we discuss a topic that feels pressing.

This July, we kicked off our Fall 2025 Dinner and Discussion Series with the topic: In competitive and high-achieving environments, how can we help our kids succeed without losing our (and their) humanity? Ultimately, we wanted to explore whether we can motivate our kids to be hardworking and successful without pushing them into anxiety, burnout, or depression – particularly since we are lucky enough to live in an affluent, high-achieving community.

A few years ago, after reading Jennifer Breheny Wallace’s book, Never Enough: When Achievement Culture Becomes Toxic and What To Do About It, I knew I wanted to get ahead of this topic while my children were still little enough for me to establish parenting habits that were helpful.

(Aside: If you haven’t read that book and you live in an affluent community or high-achieving school, I highly recommend that you grab a copy.)

As an educator, I was already aware of similar findings from the work of Suniya Luthar, who uncovered the surprising link between high-achieving communities and increased anxiety, depression, and risk-taking behaviors. Her data rocked the world of high-achieving schools and led to some of the great work that is currently being done to support student well-being today.

At our dinner table one night in July, six of us gathered. While our children all attend the same school – an affluent, high-achieving school in Atlanta – we all came from various ethnic, socio-economic, and geographic backgrounds.

What follows here is my attempt at summarizing the conversation highlights in the hopes that readers may benefit from chewing on this concept even though they could not be there to enjoy the in-person event.

(Re)Defining Success By Generation

One important topic that came up was how to define success.

Each of us reflected that success meant something very concrete to us when we were growing up. For some, it was about achieving a title. Our parents told us we could be a doctor, a lawyer, or an engineer. Success meant letters behind our names.

For others of us, we grew up with a definition of success as financial stability.

For others, it was entering a prestigious college. Or making straight A’s. Or recognition and awards.

All of us agreed that for our parents’ generation the definition of success felt significantly more narrow than it does now.

In our generation (late GenX and early Millennial), the definition of success varied person by person.

For one, success meant that you could be in charge of your own time. For another, it meant peace.

For one, it meant living out your sense of purpose. For another, happiness.

Flexibility and choice also came up frequently as indicators of success.

Another one of us bluntly said, “Come on, y’all, success means making a lot of money.”

But I started to wonder.

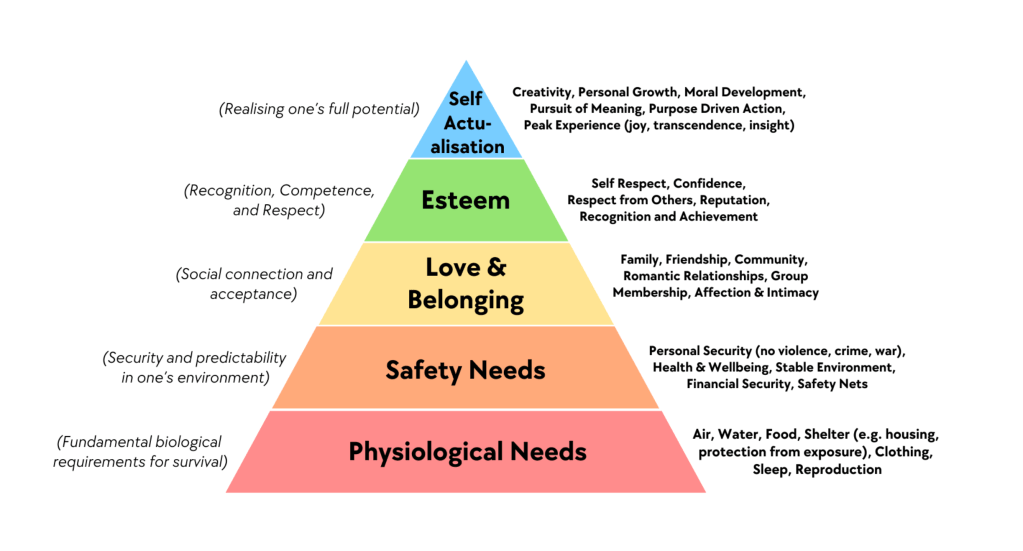

It seemed to me that we all were subconsciously dancing around Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Unlike our parents, none of us had to grow up worried about our physiological needs (air, food, water, shelter). Nor were those included in our definitions of success for ourselves or our children. In our community, quality air, water, food, shelter, clothing, and sleep are a given for the most part, thank God.

Interestingly, some of us did tie success to Maslow’s level of safety needs but not in terms of personal security or a stable environment. Those are, in our neck of America, mostly taken for granted; however, a good number of us agreed that our children needed to be able to provide financial security for themselves and to be able to have strong safety nets in place for themselves and their own children.

It was important to all of us that our children grow up to be financially stable, independent, and able to provide the same for their own families. On one very basic level, that was a shared definition of “success.”

Furthermore, many of us reminisced that our parents, or our grandparents, sacrificed self-actualization, esteem, and even personal happiness to provide that first level of success- safety needs- for us.

They sacrificed so we could one day live in neighborhoods without violence, poverty, or crime.

They sacrificed their own health and well-being so that we could have financial security.

They immigrated to America so that we could have a stable environment or opportunities that would build greater safety nets for us.

And they succeeded, evidenced by the fact that, for most of us at the table, success went beyond Maslow’s level of safety needs.

As I look back on what each group member said, their definitions of success centered more around Maslow’s levels of Esteem and Self-Actualization. At various times during the discussion, I heard that success involved:

- “Agency”

- “Self-control”

- “Purpose”

- “Choice”

- “Options”

- “Exposure”

- “Flexibility”

- “Time”

- “Perfect self-expression: does your work light you up?”

- “A posture of gratefulness”

- “Happiness”

- “Confidence”

It turns out, our generation “wants it all” for our children, and we’re betting on the fact that high-achieving environments can create that for them.

Key Tip for Parents

Take time to talk with your spouse, parenting partner, or friends and create a shared definition of success. Or at least get on the same page about what each of you believes. You might be surprised.

Ask your children about what success means to them….and what they think it means to you. Define your destination together. (Want to feel more equipped to do that? Check out coaching with Bowbend!)

The Pressure To Perform

For whatever reason, particularly in high-achieving schools, it can feel like success is a 0-sum game. An “If your child succeeds, then mine will not” mindset reigns. Perhaps it is because of our survival wiring. In the caveman times, if I found more berries on the tree than you did, it was more likely that I would survive and you would not. Yesterday’s berries somehow got translated to today’s extracurriculars, I guess.

Whatever the reason, that thinking pervades our culture, deny it though we will. And both we and our kids suffer for it.

We all acknowledged that we swim in a water saturated with comparison. This comparison culture is fueled by social media, the immediacy of fulfillment created by smartphones, and being surrounded by other fellow high achievers.

Knowing your environment is key to surviving it and thriving within it.

We all bemoaned the feeling of academic and extracurricular overload. Many families feel the need to enroll in private lessons, play multiple sports in one season, and practice like professionals for the seemingly endless list of competitions just to ensure their children will not fall behind before they get to high school.

Additionally, there is an effect we all acknowledged as real and wondered about. We all felt, at some visceral level, that our children are growing up in too much of a bubble.

We live in communities where our children’s safety needs are met. Not only that, but there is an army of teachers, coaches, therapists, and fellow parents all at the ready to ensure that their love and belonging needs are met as well.

We cannot complain that this is true. In fact, it is the dream of every parent. It is our privilege to live in an environment like this.

And yet, isn’t it ironic that instead of simply rising easily up Maslow’s ladder of needs to fulfill their needs for esteem and reach self-actualization, our children are at greater risk for stress, anxiety, burnout, and loss of joy?

For if, as parents, we are looking around, worried about keeping up with the A-list soccer-travel team player who takes private lessons on top of three practices a week, we can be guaranteed our children are taking their cues from us, however subtle we think our status-checking may be.

All of us admitted to feeling caught up in the rat race, worried that a choice “not to participate” at the highest level in elementary school would somehow set our children back, not just from their ability to achieve self-actualization, but also to ensure their more basic physiological and safety needs were met.

Our children aren’t the only ones feeling the pressure.

The Tension We All Feel

None of us want to spoil our children, but we also want to provide ample opportunities for them – especially because we can.

Some of us grew up without opportunity, not because our parents withheld it, but because our parents could not provide it.

We struggled with the tension that many of us can, at least financially, provide for, not only the basic needs of our children, but for their every desire.

In our conversation, however, we came to the discovery that our own sense of drive, purpose, and desire to achieve resulted direclty from not having every single one of our needs or whims met.

In fact, the less our needs were “guaranteed” as children, the more our intrinsic drive to achieve as adults.

So what are we to do, then, with this question: can our children develop an intrinsic drive to succeed when their first three levels of Maslow’s hierarchy are already met without them having to lift a finger?

And is this, then, the reason that so many children in affluent and high-achieving communities struggle with esteem and self-actualization? Is that just our society’s next level of “poverty?” For example, our parents fought for stability in “safety needs.” Our generation fought for the next three levels – with the lucky ones achieving all three.

Are our children fighting for the top two?

Must there be winners and losers at every level? Or is this a false dichotomy that bears reconsideration?

I’ll leave it to you to chew on, but the question bears our time and thought.

A second tension we all felt was that we didn’t want to push too hard, but we didn’t want to see wasted potential. I shared the story that an 8th-grade teacher friend of mine related to me: that teachers and parents in our school are not worried about burnout as much as they are worried about unmotivated children. What a fantastic irony, that those with the most opportunities are the ones who often least want them.

A third tension we all felt was the hidden cost of “success at all costs,” where relationships, joy, and health are sacrificed for opportunity and performance status.

One ultimate question we all kept coming back to was: Are we raising achievers or thriving human beings?

Turns out, sometimes it’s difficult to tell.

What We Learned From Each Other

My top ten takeaways from this dinner:

10) To foster motivation, increase agency.

- Kids need a sense of choice, purpose, and control. So many of the debates now about overscheduling kids, free-range kids, and over-protected kids center around this question. How much agency do children have in their own lives?

9) Encourage hard work, but model gratitude, resilience, and rest

- It’s not an either-or but a both-and. We can work hard, AND we can be balanced humans who also rest. Let’s model for our kids the lives we want them to have. Our parents didn’t always get that opportunity. Let’s not waste it now if we have it.

8) Exposure outside the bubble is key to preventing our children from becoming spoiled.

- Whether it’s traveling to other countries, visiting new states in America, or even exploring places within our own city and state where people live differently, it’s going to be crucial for our children to get outside the bubble of affluence and achievement on a frequent basis.

- Another fantastic way to help our children maintain a proper perspective is to engage in family service activities where we take time to prioritize efforts outside of “achievement.”

7) Be “in but not of” your environment.

- It’s easy to let the water you swim in color your thoughts and actions. Instead, it’s more and more crucial for parents to be aware of our environment and not let it dictate our actions. It’s a helpful place to be, not a definition of who you or your children must become.

6) Do Your Own Work

- As parents, we must manage our own anxieties, comparisons, and expectations – not pass them down to our kids.

5) Talk About It

- Defining success with yourself, your partner, and sharing that definition with your children is ever more essential.

4) Help Your Children define their target

- When children know what they’re shooting for, they’re more likely to hit it. Ask your children, “Why do you want to do this homework? Why do you think you go to this school? What do you think we hope for you? What do you want for yourself? Why is completing this assignment to the best of your ability important?” And KEEP ASKING!

3) Use Maslow’s Hierarchy to help you establish your definition of success and the steps you could take to get there.

2) Comparison is the thief of joy.

- There is an opportunity cost to competing in life. Consider the reality of your children’s school and extracurricular situation and examine the cost not just financially, but also emotionally and relationally. What are you sacrificing to keep your children competitive? And are you sacrificing it needlessly out of a sense of comparison? Could your child achieve success without sacrificing those things?

1) Children need BOTH challenge and support.

- There is actually a zone of optimal learning that is at the top end of their limit and just beyond what feels comfortable. This is not an area we can coast in if we swim in the waters of high achievement. Without intention, the currents of laziness and entitlement or the riptide of burnout can sweep our children away before we know it.

On a Final Note

For those of us for whom success in school meant getting straight A’s, matriculating into a “good” college, and getting a “good job” in finance, medicine, or the law, and then….

Artificial Intelligence is an impending atom bomb that is about to explode that definition of success.

If it hasn’t already.

So it is even more crucial for us to determine – with our children – what success might look like, particularly in the present age of A.I.

Want more resources? Follow for parenting topics at @epdwilliams and for schools @bowbend_consulting

Checkout Bowbend Consulting for more resources, coaching, and workshops.

Leave a comment